Gather us together - any of us that lived here on that sunny blue-sky day in May 1980 - and we will tell you where we were, what we were doing the day "the mountain" blew.

Forty-five years ago today, she changed the way we thought about our landscape as dramatically as she rearranged the landscape itself. We can no longer take these snowy white gods for granted.

We have been told in no uncertain terms.

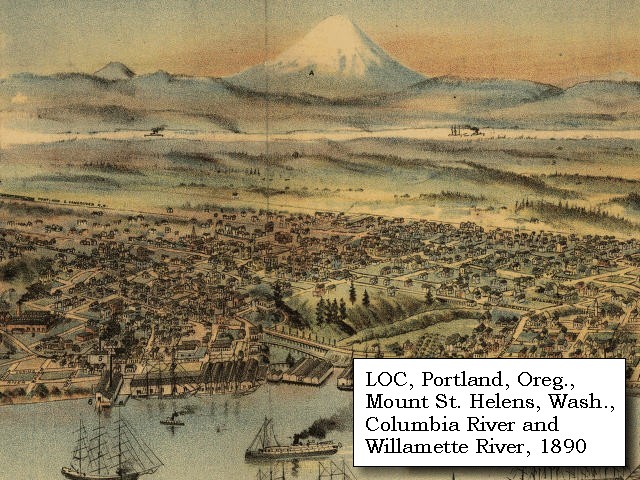

Before that year, of course, Mt. St. Helens wasn't "the mountain," but just one of several that dotted the view, along with Mt. Adams and Mt. Hood - Loo-wit, Pahtoe, and Wy'east in Native American legend.

Loo-wit was a magic mountain of slow time - berry picking in the spring and summer and a cool mountain lake for swimming. She of the generous campfires. She of youth and beauty - the prettiest of the mountains, it was always said.

It was jagged Hood - Wy'east - that had been rumbling longer, with little quakes now and then just to let us know he was sleeping, not dead.

According to legend, Wy'east was one of the great spirit's two restless, quarreling sons. The sons made the ground shake as they hurled rocks at each other. Covered with skiers, painted in Portland landscapes, Hood was the mountain everyone said would one day blow. He was the one we feared.

According to legend, Wy'east was one of the great spirit's two restless, quarreling sons. The sons made the ground shake as they hurled rocks at each other. Covered with skiers, painted in Portland landscapes, Hood was the mountain everyone said would one day blow. He was the one we feared.

Loo-wit - St. Helens - was the peacemaker, the homely old woman granted eternal beauty. Loo-wit -- less developed and less visited than Mt. Hood -- we took for granted her peace and hospitality.

But in the spring of 1980, St. Helens woke up, rocking and fuming, sending us smoke signals that something big was going to happen. The local news ran daily updates from her press conferences. Geologists issued warnings.

She had been at this for a few months - long enough for it all to become kind of a nervous joke.

In fact, we joked about it that Sunday morning, May 18.

In fact, we joked about it that Sunday morning, May 18.

In Lyle, Wash., a little town tucked in where the Klickitat meets the Big River, it was Pioneer Days - the annual parade and picnic celebration. On a plateau above town our 4-H leader Gail Farris, was orchestrating barrel racing and pole-bending events from the little booth in the open air arena, while we waited our turn in the field outside.

I don't remember any sound - distant thunder if anything. The first thing I recall is Gail reading a report that Mt. St. Helens had had a major eruption, and we all made a joke. Nervous laughter. The event went on. I remember thinking about volcanoes and what an eruption looked like. The only kind I'd ever seen were Hawaiian volcanoes - fountains of lava. I remembered scenes of scientists taking samples a few feet from the lava rivers. I didn't think we'd be close enough to feel any effect.

It was finally my turn at pole bending. I remember whipping around the final pole to face west, toward the finish line. I saw it then - like the biggest thunderhead I could imagine, only dark, dark gray, and low to the ground. It was so massive, so muscular - a mountain in the sky.

It seemed to be moving fast, coming our way - and my horse and I stopped dead in our tracks, frozen for long seconds, staring. Then we bolted for the gate. Outside the arena, horses and people moved like excited bees outside a hive. We rushed our horses into the barn, pulling off their saddles.

The ash began to fall like a sinful snow. My dad, a volunteer emergency medical technician and always prepared, handed out surgical masks. We drove the short distance home worrying about our horses, worrying about our friends. The windshield wipers made a sickly scraping sound against the ash.

We sat in our little trailer, tried to watch TV. We saw the gray destruction sweeping along the Toutle River - houses and trees destroyed by the lahar, an instantaneous melt of 1,000-year-old glaciers. The ash-engorged flood of flowing concrete scoured the mountainside, like a freight train, destroying or incorporating everything in its path - forests of trees, houses, bulldozers - and even crushing steel bridges. We saw the mushroom cloud looming high in the air. Live TV from Yakima, Wash., showed the city to the east of us cloaked in inky black. Outside it was dark, like dusk in midwinter - nothing like the May morning of a few hours earlier.

Later we heard them read the names of the missing. Then the dead. Snowplows pushed the ash off city streets in The Dalles, Ore. We shoveled it, swept it, but it just floated up in a gritty dust.

Pretty white St. Helens - we called her "The Mountain" now - had torn herself in half, sullied herself in dark gray. Her trees lay prostrate to her, her new geography unrecognizable. She continued to crack and rumble. And for a while we wondered if worse would come. Eventually the fear of another big eruption quieted in our minds.

The ash stayed with us, floating up from the hooftracks as we rode our horses through the fields, and blowing out of the vents in our car.

We see St. Helens every now and then when we cross the Astoria Bridge. My wife, Amy, will point to the blunted white figure upriver when the clouds part just right. But we don't think of her much, except when we sit around with friends and play "Where were you when ..." It's like the Kennedy assassination, or the Challenger disaster, or 9/11 for us old Northwesterners - a permanent landmark in our memory.

The eruption launched a revolution in science, a greater understanding of how ecosystems survive such events, how nature can recover from devastation. How chaos is the melody of vigorous life.

It changed our thinking too. In many ways, Loo-wit taught us more about life than death. In this generous fire, we learned so much.

It changed our thinking too. In many ways, Loo-wit taught us more about life than death. In this generous fire, we learned so much.

Love of nature is nothing without respect. Loo-wit seduced with youth and beauty, but it was her power that made the ground beneath our feet. Mountains - our mountains - are living things, and we are frighteningly humble in their presence.

It's hard to believe that was 45 years ago.

It is hard to believe we could ever take a mountain for granted.

It is hard to believe we could ever take a mountain for granted.

A version of this essay originally appeared in the Christian Science Monitor in 2005. You can find it online in its original form here.